The exit of KOKO Networks from the Kenyan market marks one of the most significant disruptions to the country’s clean-cooking ecosystem in recent years. The shutdown affects both household energy access and livelihoods, raising fresh questions about the sustainability of climate-financed business models in Africa.

KOKO’s business model

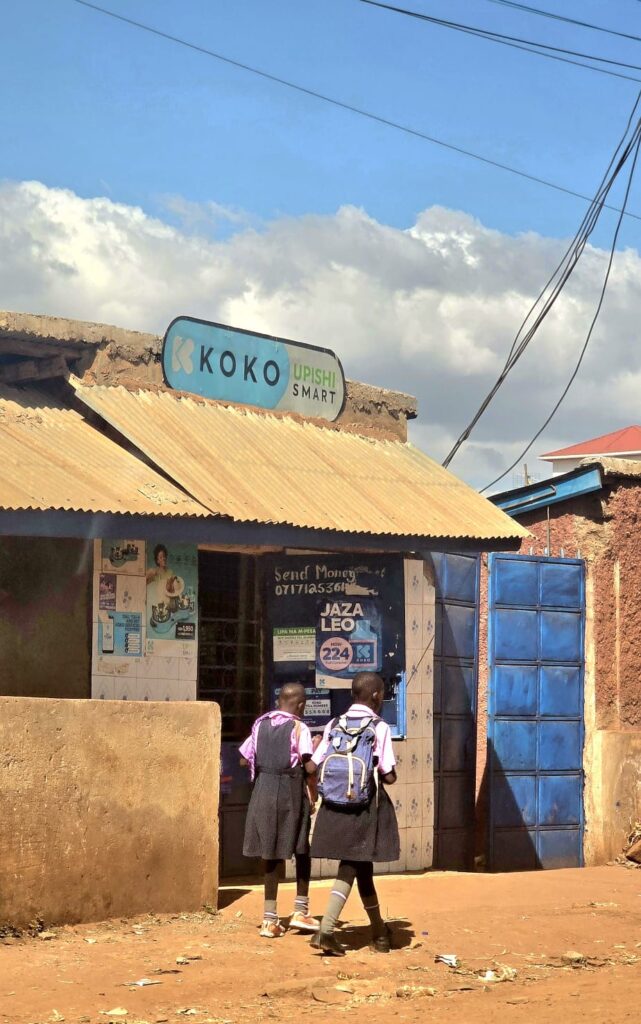

KOKO built a technology-driven, pay-as-you-go cooking system designed specifically for low-income urban households in Kenya. Customers purchased a smart bioethanol stove at a highly subsidised price and refilled fuel in small, affordable quantities through automated neighbourhood fuel points.

The company partnered with established fuel retailers, including Vivo Energy, to host its dispensing infrastructure. However, KOKO’s real commercial engine was not fuel sales. The model relied on carbon credits generated by replacing charcoal and kerosene with bioethanol. Carbon revenues were expected to subsidise both the stove hardware and the daily cost of cooking fuel.

Homes and jobs directly affected

At its peak, KOKO’s network served an estimated 1.5 million households that depended on bioethanol as their primary cooking fuel. These families now face the loss of one of the few affordable clean-energy options available at scale in low-income settlements.

Beyond consumers, the closure has employment implications. Approximately 700 direct employees are affected, alongside several thousand independent agents and retail partners who operated or hosted KOKO fuel points across major towns. For many of these micro-entrepreneurs, the fuel stations represented a steady secondary income stream.

In total, both directly and indirectly, the livelihoods of thousands of workers and small business operators are linked to the shutdown, while more than a million households must now seek alternative cooking fuels.

Assumptions behind KOKO’s market entry

When KOKO entered the Kenyan clean-cooking market, it assumed that international carbon markets would provide a stable and predictable revenue flow to support daily household energy use. It also expected fast and reliable regulatory approval for high-value carbon credits and strong policy alignment with national clean-cooking targets.

These assumptions proved fragile. Delays and uncertainty around carbon credit authorisation disrupted cash flows and exposed the company to financing risk.

Implications of KOKO Networks exit

The immediate risk is a return to charcoal and kerosene, fuels that remain cheaper in the short term but impose higher long-term health and environmental costs. From a national perspective, the closure weakens confidence in private-sector-led clean-cooking investments and highlights the vulnerability of models that depend heavily on climate finance.

Did the model work in other African markets?

Kenya remained KOKO’s only large-scale commercial deployment. Although the company explored expansion into other African markets, replication was limited. The heavy infrastructure requirements and reliance on complex carbon-market approvals made rapid regional rollout difficult.

For investors and policymakers, the KOKO experience offers a critical lesson: clean cooking in Africa can scale but long-term sustainability cannot depend on carbon finance alone.